I hope to study further, a few more years or so

I

also hope to keep a steady high - ooh yeah yeah yeah...

Mid-century American history was, for a time, thought to be a confusing maelstrom of politics and violence, of war and peace. A time when radical ideas emerged. When the past clashed with the future.

But now, the history of that generation is viewed through a different lens.

Here, in the future, the veil has been lifted. We see the complex contexts of communism and colonialism. We can better understand how the brutality of the war reflected strategies adopted by generals from World War II; holdouts from a time when it was considered acceptable to firebomb civilian cities.

We've always known that our soldiers were heros - fighting and dying in a place that many considered the wasteland of a generation. Now we know it unconditionally.

But there were others who we might also remember differently - now that we can look at the past through a future lens. That there are other heroes - ones who fought in their own way: for our soldiers to live, to come home. They painted signs that said "make love, not war." They protested, held hands and put daisies in the gun barrels of the National Guards.

They didn't know what we know today. They did it anyway.

They didn't know what we know today. They did it anyway.

From the sign-painters and protesters, the nation's conscience began to appear; radiating from our nation's younger, better angels. It flashed on college campuses; in protests, chaotic

disruptions, gatherings and, sometimes, with a certain violence.

This new collective conscience was coalesced, memorably and

beautifully, by art and music.

It had a soundtrack by Jim Morrison and The Doors, the

Who and the Rolling Stones. Joan Baez.Poetic voices. Hippie symphonies. Beautifully blended chords and bass tracks and keyboards.

Like the Who's classic tantrum about teenage wastelands.

It had a screenplay written by Martin, Robert, Timothy and others; an historic collection of philosophers, fearless dreamers and existential thinkers.

Are you optimistic 'bout the way things are going?

It had a screenplay written by Martin, Robert, Timothy and others; an historic collection of philosophers, fearless dreamers and existential thinkers.

Nixon famously despised it - and later, to his regret, he

simply disregarded it. Dissonance was attacked with rhetoric, racism,

belittlement and shame. Mistakenly - and purposely - righteousness was cast in

the context of drugs, pot and ignorance.

But the coffins kept coming home, draped in flags; and the

cameras rolled. The images indelibly imprinted and energized the young, beaded

and bell-bottomed. The result was a movement that would define their

generation.

From the past, the words and music can remind us - in an instant - of just how special those days - those moments - really were. They were us at our best.

And even though perhaps we didn't know it then, we do now.

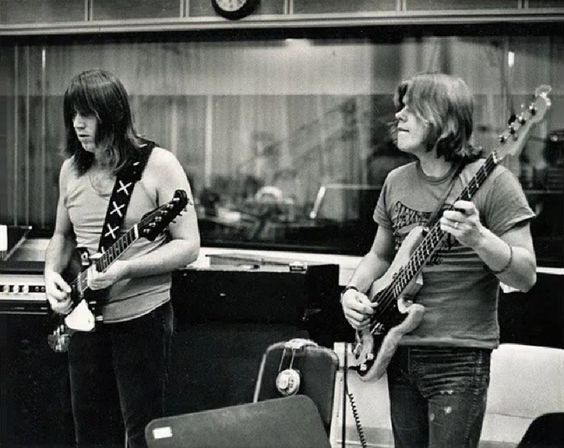

For me, there is this... "Dialogue parts I & II," written by Robert Lamm in 1972. It featured Terry Kath and Peter Cetera of the group Chicago. Terry, on his lead guitar, sent Lamm's words and chords across the studio to Pete, who responded with bass guitar and a kind of glorious inspirational naïvete.

And even though perhaps we didn't know it then, we do now.

For me, there is this... "Dialogue parts I & II," written by Robert Lamm in 1972. It featured Terry Kath and Peter Cetera of the group Chicago. Terry, on his lead guitar, sent Lamm's words and chords across the studio to Pete, who responded with bass guitar and a kind of glorious inspirational naïvete.

It's goose-bumpingly stirring. To sing along and replay this anthem, over

and over, is to glimpse moments in 1972 when heroes came in more than one form.

Are you optimistic 'bout the way things are going?

No, I never, ever think of it at all

Don't you ever worry, when you see what's going down?

No, I try to mind my business, that is, no business at all

When it's time to function as a feeling human being, will

your Bachelor of Arts help you get by?

I hope to study further, a few more years or so. I also hope

to keep a steady high - ooh yeah yeah yeah

Will you try to change things, use the power that you have,

the power of a million new ideas?

What is this power you speak of and this need for things to

change? I always thought that everything was fine - everything is fine

Don't you feel repression just closing in around?

No, the campus here is very, very free

Does it make you angry the way war is dragging on?

Well, I hope the President knows what he's into, ooh I just

don't know

Don't you ever see the starvation in the city where you

live, all the needless hunger all the needless pain?

I haven't been there lately, the country is so fine, but my

neighbors don't seem hungry 'cause they haven't got the time

Thank you for the talk, you know you really eased my mind. I

was troubled by the shapes of things to come.

Well, if you had my outlook your feelings would be numb,

you'd always think that everything was fine.

Everything is fine.